What are computer networks?

A computer network is a collection of interconnected computer systems which ‘talk’ to each other by exchanging data. Connecting computers to form computer networks has had a huge impact on our lives. The internet is a network of networks. Think how limited our use of technology in school would be without it. Think how frustrating it is when we have no data signal for our smartphones, or no Wi-Fi for our laptops.

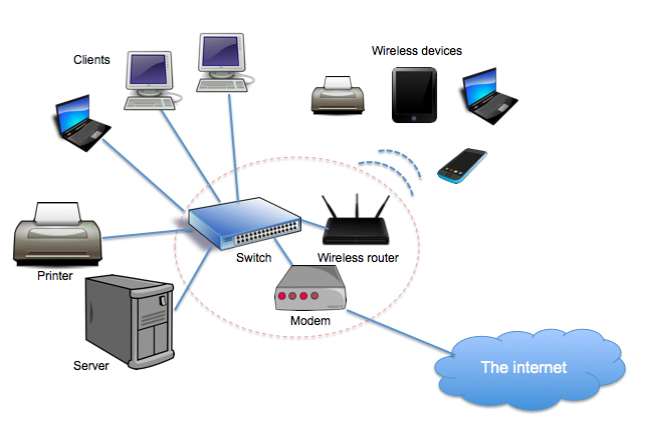

The computer network within your school possibly consists of only a few computers. Networks of this size are called local area networks (LANs). The following diagram shows the devices comprising a typical LAN; the three devices in the centre of the picture are typically combined in a home network (see below).

The layout of devices in a LAN.

A LAN enables:

A server.

A client is any computer system on a network which uses the services provided by the server. For example, each classroom might have a computer at the front of the class which is linked to the school’s LAN and which is used with an interactive whiteboard. Teacher and pupil laptops will also likely be configured to access a school’s LAN to enable internet access, printing and the saving of work to a shared area. Other devices such as tablets or phones may also be clients, since these too can connect to the LAN.

Possible clients in a network.

Switches and hubs are used to connect the various devices on a network, reducing the amount of cabling required.

A server in a school's LAN.

A modem provides access to the internet by converting the format of data in computer systems to one which can be transmitted along telephone lines to your internet service provider (ISP). It also performs the reverse conversion for data coming in from your ISP.

A range of devices may connect to a LAN wirelessly. These could be clients, such as laptops, tablet devices and phones. Devices providing services to the network (e.g. printers) may also connect wirelessly. A wireless router enables devices to connect to the LAN by routing data across a wireless connection.

Wide area networks (WANs) are created when lots of smaller networks are connected together. The largest WAN of all is the internet. Note that the internet is a physical thing: it’s the cables and fibres, transmitters and receivers, switches and routers – and all the rest of the hardware infrastructure – which connect networks of computers together. The World Wide Web is the information on the internet, displayed as web pages whose content is stored on web servers and viewed across the internet using web browsers such as Internet Explorer, Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox. So, the World Wide Web is one example of an internet service.

The internet has been designed to do one job: to transport digital data between computers. This information might take the form of a web page, an email or a video call but all of it is in binary code consisting of strings of the digits 0 and 1, transmitting as on/off or high/low electrical or optical signals. Binary code is similar to the Morse code used for the telegraph in Victorian times, but it’s much, much faster. A good telegraph operator could work at maybe 70 text characters per minute, but even a basic school LAN can pass data at 100 million on/off pulses per second – sufficient for some 12.5 million characters per second. One transatlantic fibre connection has the capacity for up to 400 billion characters per second!

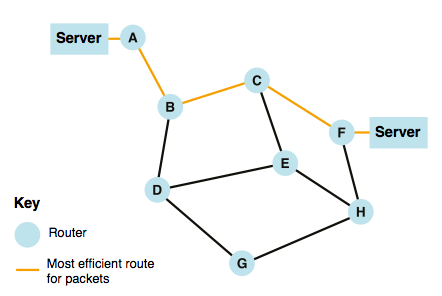

To be sent efficiently, digitised information is broken down into small chunks – data packets – which pass quickly through the internet and are reassembled at the receiving computer. These packets can take any route from sender to recipient, although there’s generally a most efficient route which all the packets take. The process happens so quickly that high-definition video can be streamed from the internet, normally without any glitches.

A sample network. (From "QuickStart Computing: a CPD toolkit for Primary teachers".)

When you type a URL address (such as www.bbc.co.uk) into your web browser, you send a packet of data requesting that the content of that page be returned to you over the internet. For this to happen, the Domain Name Service (DNS) converts the requested URL into a numeric IP (Internet Protocol) address; the DNS itself uses the internet to look up this numeric address in the equivalent of huge phone books. The requested web page content again consists of data packets, each of which carries a destination IP address. So, routers can easily and correctly pass on each packet.

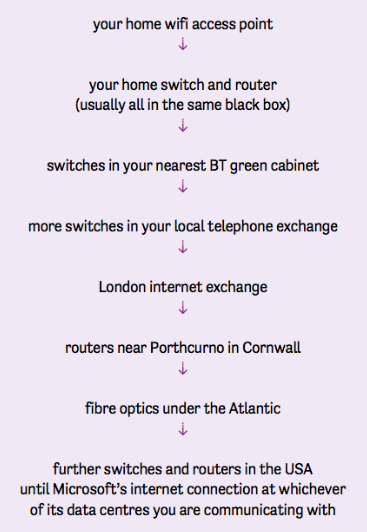

The journey of a packet of data from your home computer to one of Microsoft’s server farms might look something like this (from “QuickStart Computing: a CPD toolkit for Primary teachers”):

The journey of a packet of data from your computer to one of Microsoft's server farms. ("From QuickStart Computing: a CPD toolkit for Primary teachers".)

To be able to send sensitive information – such as passwords or bank account details – secretly via the internet, it’s important to encrypt the data first. (It will be decrypted when it reaches its destination.) This happens automatically when using web addresses commencing “https” (HTTP Secure) – you’ll see a little padlock displayed in your browser’s address bar.

Why are computer networks important?

Computer networks enable multiple computer systems to share software, printing, internet access and an area for saving files, reducing organisational costs. Networks facilitate file-sharing and collaboration. Servers can be set up to create automatic backups of content stored across a network. The internet itself provides a wide range of services which we use and depend upon daily. The term “Internet of Things” has been coined to describe the multitude of computing devices embedded in goods and networked to the internet. One example is the thermostat which can be controlled using your mobile phone. South Korea’s Songdo International Business District is a “smart city” where sensors throughout collect data which feeds back to the management of resources and assets. Looking to 2020, Gartner has estimated that there’ll be nearly 26 billion devices on the Internet of Things, whilst ABI Research has proposed there may be 30 billion devices wirelessly connected to it (the “Internet of Everything”).